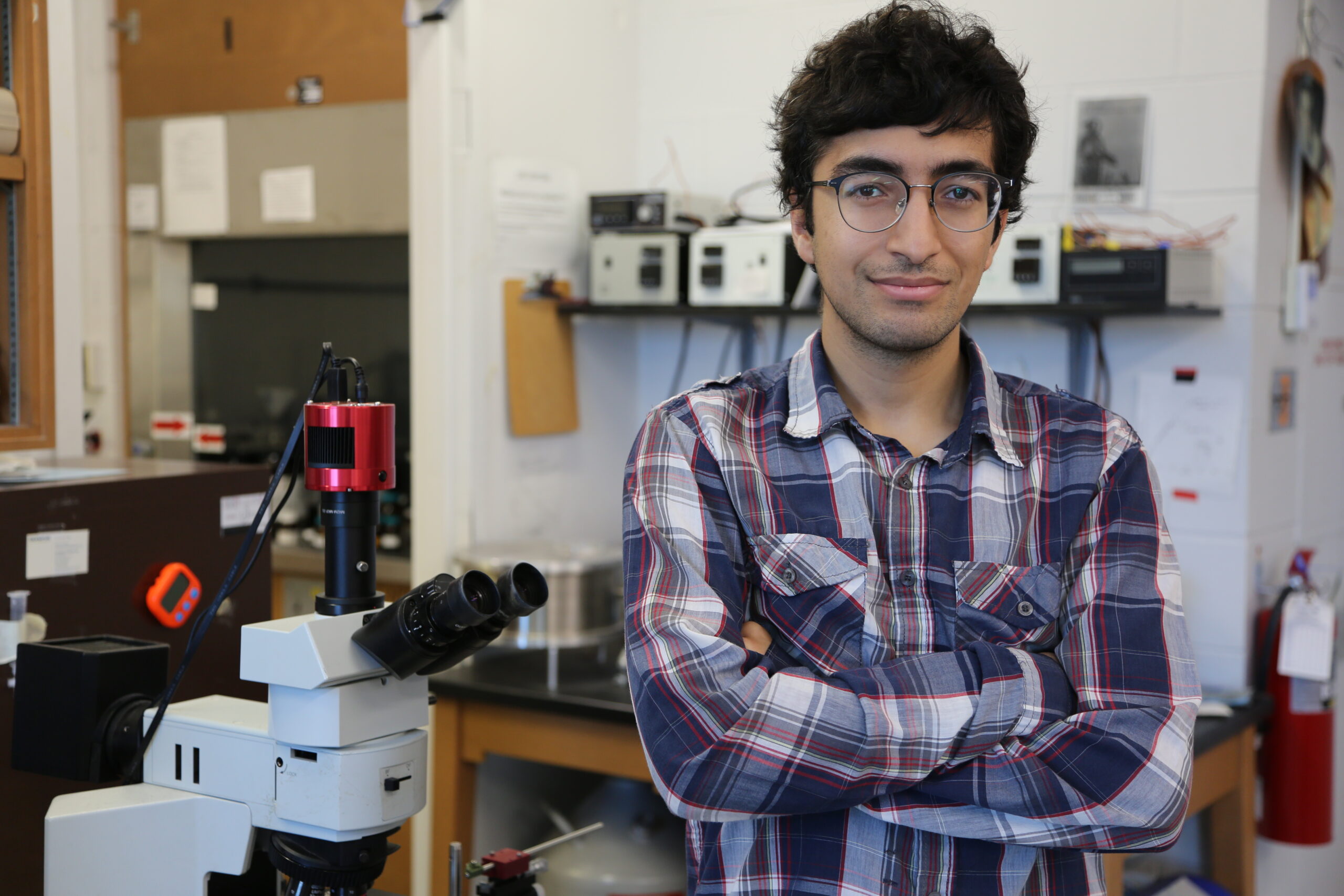

Unpaving paradise and putting in ponds – Science PhD student coordinating restoration and conservation efforts on campus

Noah Stegman couldn’t believe what he found at McMaster’s latest environmental restoration project.

Five vernal ponds were added to the West Campus last November – Noah oversaw the project as McMaster’s Coordinator of Natural Lands Restoration and Conservation. The ponds are on a strip of land between the baseball diamonds and where Cootes Drive bends towards Dundas. The shallow seasonal ponds were designed to fill with melting snow, spring rain and groundwater and then dry out. That makes it the perfect habitat for amphibians and insects – there’s no risk of getting eaten by fish.

Noah, who’s a PhD student in Earth and Environmental Science, visited the ponds in early April with low expectations. It had been a warm, nearly snow-free winter. And it usually takes a few years before amphibians make themselves at home. But the ponds were full of water and teeming with life. There were frogs, toads and tadpoles galore. “I couldn’t believe how quickly the ponds had started working. They were well ahead of schedule.”

The ponds are part of the ongoing restoration of the West Campus. The area where hundreds of students, faculty and staff park their cars and play slow pitch was once wetlands with a creek and floodplain. It was also home to the Coldspring Valley Sanctuary, a popular destination with its bird diversity and wet woodland habitat. Visitors were welcome to walk the trails but were reminded not to enter with “an axe, a gun or a dog unleashed”. There was an elm-ash woodland, “dense vine tangles”, open grassland and a bird food plantation.

McMaster began buying the sanctuary lands from the Royal Botanical Gardens in 1963. To make way for surface parking, the forest was eventually cleared and the Ancaster / Coldwater Creek was redirected. Lot M and the Facilities Building opened in 1974, followed by Lot P. The vernal ponds are located on a wetland that was filled in decades ago and then forgotten.

Restoration of the West Campus started around 2014, the same time Noah joined McMaster as an undergraduate student taking Earth and Environmental Science with minors in Biology and Geographic Information Systems. He remembers only going outside for a single lecture, even though the campus is surrounded by nature.

All that’s changed for Noah – he spends a lot of time outdoors. Along with coordinating environmental restoration and conservation, he’s the graduate representative on the President’s Advisory Committee on Natural Lands and McMaster’s representative on two subcommittees with the Cootes to Escarpment EcoPark System. He manages trails for the McMaster Forest and supervises a crew of student interns. He’s also the Coordinator of Nature at McMaster and an advisor and former president of the McMaster Outdoor Club.

Working on restoration and conservation projects lets Noah put his head, heart and hands to work. He also gets to consult and collaborate with community partners who share his passion for conservation.Those partnerships were crucial to building the vernal ponds, which were funded with a grant from the Parks Canada National Program for Ecological Corridors Cootes to Escarpment EcoPark System Pilot Project.

Approvals were needed from both the Hamilton Conservation Authority and Hydro One – powerlines cross over the ponds which meant trees were out and shrubs were in.

Elders from Six Nations of the Grand River and Indigenous Studies faculty were also involved right from start as equal partners – McMaster is, after all, situated on traditional territories shared between the Haudenosaunee confederacy and Anishinaabe Nations. “Too often, Indigenous communities are brought in as an afterthought on environmental restoration projects even though they are the original stewards of this land. We weren’t going to make that mistake in building the ponds.”

The project adhered to the Indigenous approach to restoring degraded lands. Instead of spraying herbicides or ripping everything out of the ground to start over with a blank slate, restoration is gradual and builds on what’s already there. “You go with what the land wants and is telling you,”says Noah.

While there are invasive species around the ponds, there were also a surprising number of native species – including a stand of rare grasses that are found in just two other locations in Hamilton.Crews of volunteer students helped clear out invasive species, plant hundreds of shrubs and thousands of seedlings, including Indigenous cultural plants that will eventually be harvested.

The plan is to turn the five ponds and the surrounding land into an outdoor classroom and living lab for students with Indigenous Studies and in the Faculty of Science. There are also plans to bring a marsh back to the West Campus just beyond the ponds that will provide another nesting habitat for turtles.

Environmental restoration was only a whisper when Noah joined McMaster 10 years ago. He says McMaster has embraced conservation in a big way and has become a leader among universities. Lots of classes now routinely head outdoors. And there’s growing and sustained support for restoration projects.

“Lots of people want this work to succeed. I constantly get emails from people who walk, bike and drive past the ponds and appreciate what the university is doing there. McMaster has come a long way and I’m proud to have played a small part.”

PhD student, Sustainability

Related News

News Listing

PhD graduate an emerging leader and role model in responsible artificial intelligence diagnostics

Grads to watch, PhD student, Research excellence

November 15, 2024

PhD graduate makes the case for offering music therapy to stressed students- “put the broccoli in the brownie”

Grads to watch, PhD student, Research excellence

November 14, 2024

Grad to Watch: Research, academic and outreach all-star Hamza Khattak

Grads to watch, Outreach excellence, PhD student, Research excellence

November 12, 2024